Sophomore year Skip and I lived in that ZBT grand mansion on the edge of the gorge. We found it easy and comfortable to live in two parallel worlds -- the white fraternity world, and the black student social and political world. That Fall 1966, and also Fall 1967, an unprecedented number of black students arrived in Cornell's freshman classes, and there was something different about them. Many were southern and rural, and came from places like Little Rock, Arkansas and Dayton, Ohio. They arrived on campus with an already honed sense of militancy born of racial grievance, and their leaders quickly evinced intense dislike of Skip and me. Just hearing us talk, it seemed, or seeing that we were comfortable wherever we went on campus, angered them. Skip and I, they said, were "not really black". In one sense they were arguably right about Skip -- he transcended race and saw the best in every person. Skip and I refused to let them intimidate us, and on two occasions the verbal animosity deteriorated into physical fist fights. Skip and I stood back-to-back and fought them, two of us against three of them, and taught them the hard way to respect us. Skip Meade was a loyal friend one could depend on to cover one's back when the going got tough.

Junior year on April 4, 1968 Skip and I were riding in his Volkswagen "Bug"near the girls' dorms (of course, where else would we be!), and the radio was playing "Ain't No Mountain High Enough" by Marvin Gaye and Tammy Terrell. The music stopped abruptly, and an announcer said Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot in Memphis. We looked at one another, and Skip slowed the car but did not stop. After that it seemed to us that America was on the brink of revolution. Major riots, which some observers called insurrections, in over 100 cities; Robert Kennedy assassinated; massive antiwar protests met by severe police violence in Chicago at the Democratic presidential nominating convention. It seemed like America was coming apart at the seams, and black students at Cornell initiated self-defense measures by gathering firearms at our 320 Waite Avenue campus meeting house. Skip Meade felt a moral and historical obligation to be prepared to fight on the side of black liberation.

In April 1969, our senior year, Skip and I participated in the black student occupation of Willard Straight Hall, the Cornell student union building. When white Delta Upsilon (DU) fraternity brothers entered through a side window with intent to evict us from the building, we fought them and threw them out. Rumors spread that DU was going to come back armed, so that night we brought in our weapons for self-defense. Skip and I were two of the students who snuck out of Willard Straight in the darkness, evaded being seen by police, retrieved our weapons from 320 Wait Avenue across campus, and snuck them into the Straight. The situation grew increasingly tense over the next day and night, with state and local police units marshaling forces in downtown Ithaca. I could see increasing uncertainty and apprehension in the eyes of some black students, but Skip was calm and committed. Skip Meade knew that we were caught in a historic moment we had not asked for, but that we had to have the courage to face whatever came our way.

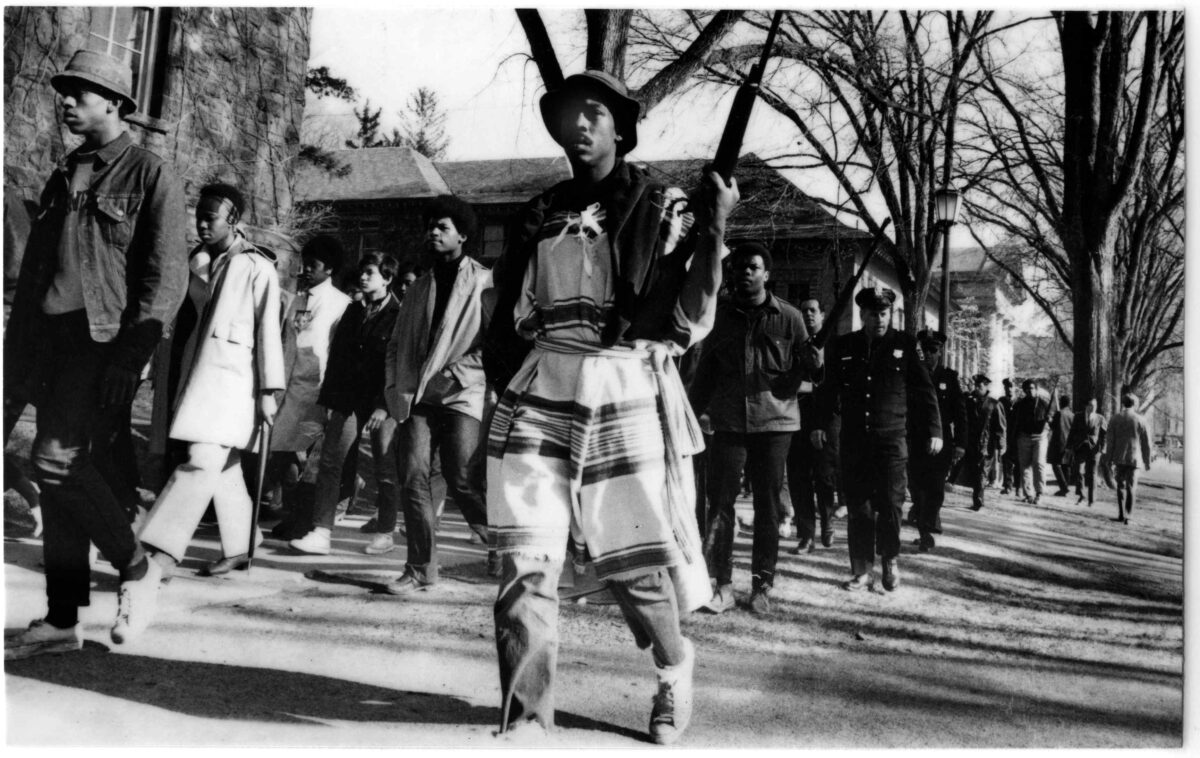

University administrators negotiated a settlement and black students agreed to leave the building, but we refused to disarm. Skip looked like Clint Eastwood in a spaghetti western -- floppy hat, woolen poncho he made from window drapes in the Straight (kudo's to Skip's artistic creativity in the midst of crisis!), cigar clenched between his lips, rifle at the ready in the crook of his arm. When the Straight's massive double doors opened and we stepped out into the day, we heard someone proclaim "Oh my God!" and we were met by furious clicking of camera shutters. One of those photos won a Pulitzer Prize for Steve Starr from

Associated Press and became the cover of the next Newsweek magazine. We marched across campus in military formation. Armed black male students were in front, rear, and both flanks of our column; in the middle were women and other unarmed students. Skip and I both swelled with pride in this display of solidarity and courage, and its explicit repudiation of hundreds of years of American history of blacks cowering in subjugation and fear. Skip understood that one reason blacks had suffered 400 years of oppression in America was that not enough had been willing to fight and die for respect and equality. Skip Meade showed no fear when the random wheel of history brought us to that unforeseeable crossroads where we faced that challenge.

Skip wrote an essay about those moments in the Straight. Writing in the third person about his fictional persona named Manchi, Skip said: "Manchi had another belief. He thought that we each decided to accept the responsibility of being one of 'the chosen'. He had decided for himself that he was called to give, even his life if necessary, in the struggle to establish justice and right. As he continued his ritual [of cleansing his body] he thought to himself. Who will see me in my death? It will be my family. Dad will ask to see my body. Boy, was he mad over the telephone! When I'm dead, he will travel here and demand to see my body. I want him to notice that I was cleaned. I want him to be able to sense that I was prepared to go. Martin said it best, "...a man has not lived until he has found that something for which he will die; and until that decision is made, though he may live to 95 years old, the mere cessation of life is only a belated announcement of an earlier death of the spirit."

In closing, Skip Meade was a man of love, and honor, and courage. We are all blessed that God brought Skip Meade into our lives. Skip Meade was not afraid of death, and his spirit has not died but lives on in each of our hearts.